Want to read more reviews? John Wiswell has the full blog hop listing.

2013 has been a weird year for reading. On the one hand, it hardly feels like I've read anything at all (and, going by my Goodreads list, this is totally true between the end of July and the end of December, where I finished two books in three days). On the other hand, I've read more than I thought I did, and I've been reading more shortform stories than I did in the past.

Another thing that was weird is that it seems I've been reading mostly men authors this year. I honestly don't pay attention much when I'm picking up a book, but it's uncomfortable that this happened the same year Alice Munro was the first Canadian Nobel Prize for Literature, the same year that David Gilmour publicly showed an inability to differentiate between "great literature" and "literature by men", the same year that the "fake geek girl" meme exploded. In previous years my list has had a majority of women authors. Maybe I need to actively re-balance next year.

A third item to consider before getting to the list: I read a

lot of murder mysteries this year. Science fiction is and likely always will be my favourite, but mysteries were my first love. That's simply because I was one of those kids who jumped to reading full novels as soon as possible. The grown-ups gave me Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie to read because they figured there was relatively little sex in them, and no worse violence than I saw watching

Superfriends or

Emergency!.

I call mysteries my "candy" reading; not because I think they're superficial (more on that in the reviews), but because they're a similar pleasure to sitting down with a box of really nice fancy chocolates. They're great for stress relief. This year had more stress in it than other years.

One final point: I've always maintained a policy that I never include books I've beta-read or read ARCs for in these lists, just because it means I've had a certain amount of contact with the author and that means I'm less objective etc. etc. I think next year I'm going to toss that out and just disclose. This year I included a book by Vicki Delany, who personally sold me the first Constable Molly Smith book I ever read. It's the only time I've ever had a conversation with her, so I'm not counting it.

Here's the list.

Montaro Caine, Sidney Poitier

Yes, it's that Sidney Poitier, the Hollywood actor (and former ambassador to Japan). I haven't read any of his other books, but this one caught my eye because it's science fiction. While set mostly in the present day, the science fiction tradition the book belongs to was more prevalent in the sixties and seventies — it's not afraid of leaving things unexplained, it's not afraid of getting mystical, and it definitely posits that our interior lives and the "big picture" of what's going on in the universe are all part of the same experience. I could tell you about the plot and the characters: there are mysterious coins found clutched in just-born babies' hands, mathematical geniuses on the autistic spectrum speaking prophecy, and a metallurgist CEO discovering his real fate, but really this is a book of ideas.

What I found fascinating about it is that so much of it is concerned with consumerism and capitalism. I'm trying to avoid spoilers here, but a series of incredible events occur right at the beginning — the sort of thing that would have launched new religions at one time in history. But all the characters are so mired in the exchange of capital for goods and services that the few who recognise the significance of what has happened get physically threatened for breaking with the status quo. I spent most of the middle of the book wanting to give certain characters a good shake and tell them they should stop and think about what the hell they're buying and selling. But of course, that's the point.

Poitier's prose is crisp and unadorned; the book sometimes reads like a documentary transcript. There are occasional brief bursts of poetry, though, half a sentence here or there, and they're lovely. Given the "out-there" content, the flat delivery worked for me.

At the end of the story, I felt like I'd just read a fable I'd only partly grasped the moral of, but was quite happy to ponder further. Just before I started writing this review, I typed "Montaro Caine" into an anagram generator. It had occurred to me that while he is an important character in the book, he's not always the

central character — it wasn't an obvious choice to title the book for him.

In the top five generated anagrams was "Arcane Motion", which is a phrase that has a lot to do with the events described in the book. It made me wonder.

Wool Omnibus, Hugh Howey

I read

Wool just to find out what all the fuss was about, and because so much of the hype was about how an indie author had made it to the best-seller list.

This is definitely a case where the book lives up to the hype.

The basic premise: an entire society of survivors have been living in an underground silo for generations. Their culture is a mishmash of American-style military labour divisions, 1950s utilitarianism run amok, and European medieval guild organisations. They have one, and only one, form of enacting capital punishment. The condemned are put into hazmat suits and sent outside to die of exposure to the poisoned elements.

Except then we find out there's more to it than that.

Wool is working in another classic science fiction tradition, one that's grittier and grimmer than

Montaro Caine. In

Wool, the world has shrunk down so far that the "big picture" is the silo. This is a society where most people only ever see the same two or three floors they live or work on. For holidays they visit the upper levels and get to see the environmental horror that is "outside".

Wool raises some excellent questions about information distribution, societal structures, and what "freedom" means. It explores some answers, but doesn't give a pat affirmation to any of them. It was a great book to read in this year of the Edward Snowden NSA revelations.

Negative Image, Vicki Delany

Negative Image is one of a series of mysteries centred on the character Constable Molly Smith, who works in the fictional Trafalgar, British Columbia. I started reading this series last year. The copy editing misses (there's always a few in every book) drive me crazy, but I love the characters (especially Molly), the plots, and the setting. My paternal grandparents used to live in Kelowna when I was a kid, and we'd visit them every summer, so I really appreciate having some fiction set in the interior of BC. It's a setting that should be used in books and films more often, in my humble opinion.

One of the things I find interesting about this series is that Delany sticks to more realistic events in her plots, including the violence. I suspect Trafalgar has more fictional murders than any real town of the same size in BC, but each one is investigated with proper attention paid to actual Canadian police procedures.

With the attention to detail on the violence comes a greater attention to detail on other, related matters. The books make it clear that Molly Smith gets more flak, from the criminals, from the local citizens, and from some of her own colleagues, because she's a woman. This might not sit well with some readers, but I've yet to read anything in any of the books which suggests Delany is pushing it too far. All of it rings true, and the types of incidents Delany depicts are congruent with the culture of a small, relatively isolated city. I lived in a city like that for twelve years.

I'd recommend any of the Molly Smith books if you like the

Wallendar books, but feel like something a little less heavy and world-weary.

Jar City, Arnaldur Indriðason

Arnaldur Indriðason's series of Erlendur mysteries is another set of books I've been working my way through since the end of last year. Erlendur is like the opposite of Molly Smith: he's a senior, experienced detective, rumpled, perennially grumpy. A friend of mine called him an Icelandic Columbo, and that's not a bad description.

All of the Erlendur mysteries draw major plot points from history. Often, as is partially the case in

Jar City, Erlendur is working on a cold case. Sometimes, and this is particularly relevant to

Jar City, the crime has just happened, but it is motivated or influenced by past events. It's like the famous William Faulkner quote: "The past isn't dead. It's not even past." There are no fresh starts, for the victims, for those who commit the crimes (here, as in other Erlendur stories, to a large extent victims themselves), or even for the police force trying to keep order and enact justice.

I'd recommend

Jar City in particular just because it raises serious ethical and philosophical issues which tie directly into the main murder plot.

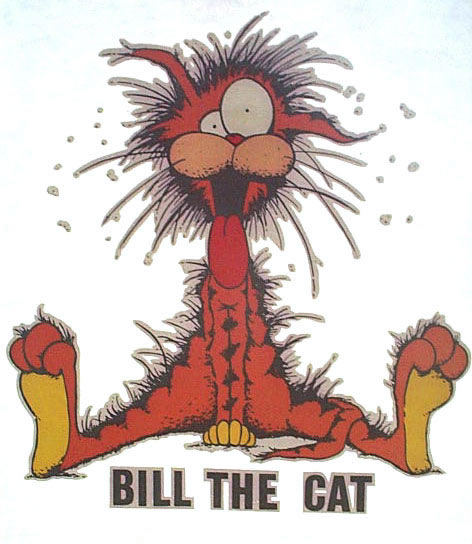

The Bloom County Library, Vol. 4, Berke Breathed

My brother Steve has been gradually giving me each volume of

The Bloom County Library as they get released; Vol. 5 is already out, so I'm one behind right now.

I can't believe how relevant these comic strips from the 1980s still are today. I also can't believe how few people seem to know about them. The strips were published in major newspapers during their initial run, and had a devoted (and always underestimated) following throughout. They're still as surreal and wonderful and funny-as-hell as they were the first read through. Some of the references have gotten stale (I checked a few on Google when my knowledge of 1980s American politics failed me), but overall they hold up well. A little

too well, given that a lot of the humour is about how colossally (if hilariously) messed up things are.

Now, check this out. Miley Cyrus, 2013:

Bill the Cat, 1986:

See? Anyone alive stuck in Western culture today needs to (re)read these comics. You'll learn that Miley and Bill have way more in common than favourite musical grimaces for publicity photos. You'll learn a lot. One of the things you may learn is how long you can laugh before you absolutely need to use the washroom.

Things might not make any more sense, but they'll be funnier. I'll be checking my kitchen drawers for my Ronco Turnip Twaddler while you catch up.

V for Vendetta, Alan Moore, David Lloyd et al

I bought this ages ago, after I saw the film (yeah, I saw the film first. Bite me.). I just never got around to reading it because I knew it was going to be depressing, and it is, but it's wonderful, too. It takes place in a late 1990s that almost-was and partly-is. When the book was published, the was an entirely plausible near-future. Now it's a recent that wasn't quite... but we came awfully close, and could still get there.

It's an exploration of the dance Western democracies do with fascism, of the difference between anarchy and chaos, of free will and the greater good. There's a lot of uncomfortable material here, including (especially?) from a feminist perspective, but the story manages to walk the tightrope between depicting something nasty and endorsing it.

The artwork made me feel nostalgic. I don't read as many graphic novels as I'd like to these days, and a lot of it has to do with how much I miss the art style of the 70s and early 80s. By the early 90s both the men and the women in the comics look like they've been drawn from balloon models — the proportions are ridiculous and distracting. The men's shoulders are too broad, the women's bustlines too pneumatic. Here, with the effects of the old American Comics Code still felt if not enforced, the proportions are relatively realistic. In this particular case the story is served better by it, adding to the plausibility and verisimilitude.

The Casual Vacancy, JK Rowling

I have the paperback copy of this book, and it's almost exactly 500 pages long. That's 300 fewer pages than my copy of

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. I got through the latter book in a weekend of non-stop reading, and I loved it.

The Casual Vacancy took me five months of off-and-on reading to finish. But I loved it just as well. The book depicts the weeks following the surprise death of a progressive member of the local parish council, and the fallout caused by death.

Rowling's talent for creating well-rounded, flawed characters is very evident here. Although the reader could draw up lists of "good guys" and "bad guys", it would be problematic because all the "good guys" have major flaws, and all the "bad guys" have significant redeeming qualities.

The Casual Vacancy reminded me a lot of

Middlemarch by George Eliot, and I'm not the first person to make that comparison. I

loved Middlemarch, so it makes sense I'd love

The Casual Vacancy as well. Both of them have a big sense of time, a big sense of how personal interactions work. I really enjoyed seeing how an innocent, inconsequential action by one character could have major repercussions later on.

If you read writing advice articles, there's a lot of talk about how "good" books are "unputdownable" (a horrible neologism, but there it is).

The Casual Vacancy is "putdownable" — there was about a three-month gap between when I read the first half and when I read the second half — but I don't see that as a bad thing. It's the difference between visiting a smallish town only during the election week to fill a casual vacancy, and living there for a few months. The perspective will be different, but the latter one will be richer and allow you a greater understanding of how the place and the people in it tick.

Rowling doesn't spare any of the characters in this book. All of them get a 1,000 watt klieg light shone on them, and there's nowhere for them to hide in her omniscient third-person narrative. It can be uncomfortable for a reader, because even if no one character is like you, you'll spot your sense of humour in this one, your temper in that one, your choice of dress or diet in someone else again. Even though you're not in the novel's fictional setting of Pagford, you may as well be.

Margaret Thatcher claimed that there was no such thing as society. It seems to me that

The Casual Vacancy argues, quite forcefully, that if —

if — there isn't, then there needs to be. In its own way, this is as much a call for the end of elitist "1%" control as

V for Vendetta is.